I will be writing a memoir at some point down the line, but for now I’m submitting a small portion for a potential writing residency next year. So this post is for your magnificent feedback! This is a highly unedited, unfinished, first draft of a first essay, working title “I didn’t change the names.”

Death, Life, and the Vague Details in Between

Death came like a wave after high school, like kids were just waiting to die, unstructured by prom and midterms, weekend jobs stuffing popcorn bags at Star Video. Now came adulthood, kicked off our parents' cell phone plans and car insurance. Getting up early to pay the bills and skipping late nights swimming under the stars at Lake Sutherland. Cheap beer. Zero supervision. The curfews we'd snubbed since turning 18. All of it gone, replaced by civil service jobs, hair schools, maybe a state college if we'd gotten our act together. And while some of us packed our XL twin microfiber bedding, our first ever Costco-sized boxes of toilet paper, and flip-flops to abate the freshman-shower foot fungi, most kids in my hometown woke up September 1st with a pretty bleak outlook, their first baby-existential crisis. And then they began to die.

We didn't have social media back then, just texting on primitive phones that fit in the tiny pocket inside the pocket of our Union Bay jeans. A sentence took an hour to write, so we had to be quick, simple, to the point: "Sam dead." "Tori dead." "James dead." Every couple of months, "Yada yada dead," followed up by a phone call (we weren't afraid of them back then), or maybe we'd scuttle over to our massive Gateway computers and hop on ICQ to ask casual, non-prying questions about people we weren't really friends with but suddenly were. The 8th Street Bridge took a lot of them, 100-feet-high over the long, dark logging road below. If they did their math wrong they might land somewhere along the bluffs with internal injuries and months in a psych ward. But most didn't. Most got it right, kind enough to wait for the truckers to pass before they flew into oblivion. City government eventually installed suicide barriers after a few years, but they only really deterred the ones who didn't want to do it anyway, the ones who were "on the fence." Pun intended. Any depressed kid who grew up climbing trees would find a way, and off they'd go into whatever came next. Some were talked down if they took too long to decide. And generally only if the cop was someone they knew, someone their age, someone who likely might be the next guy hanging off the bridge in the dark. Someone who got it.

If you didn't die on the bridge, or from cancer, or in the once-in-a-blue-moon murder-suicides out in the west-end trailer parks, then it was almost always Black Diamond. Known as the "Grim Reaper," Black Diamond Road was home to more victims than the Ocean View Cemetery. Called "Black" for its ice nine months of the year, no one had ever thought to install streetlamps or really any kind of road-management along the 4.5 miles of treacherous, winding, two-lane road. So of course we spent a lot of time there. This was before GPS or Find Your Phone, when our parents spent half the night calling around town, the police departments, the hospitals, until we came lumbering home in the wee hours smelling strongly like Altoids and campfire. Most of the things that happened in the woods along Black Diamond Road stayed in the woods along Black Diamond Road, though a few feral, sometimes naked, photos make it to the surface once in a while before slipping quietly back under a mattress, or into an old album high in a closet. Saved for just the right occasion. I hope "just in case" comes sooner rather than later.

When a kid died it gave the Peninsula Daily News something to write about that wasn't girls basketball or city council meetings. Now, I don't want to say that's exciting, for obvious reasons, but we really had nothing to talk about. For a town of 18,000 people on the upper Olympic Peninsula things were surprisingly slow. Even our weather was slow, a constant drizzle that wasn't quite the record-breaking deluge of our neighbor, Forks, and neither was it the relatively kinder climate of Seattle. Once a year the fair came to town and we could talk about sheep or, in front-page news, the Clallam County Demolition Derby, but the rest of the time we settled for job-development gains (there were none) and new businesses (also none). Obituaries read like a who's who of the Lutheran Church and Kiwanis Club, and people really only read those to see why so-and-so hadn't shown up for the past few weeks. Clarity. Closure. A possible upgrade in administration. Housekeeping. But losing a kid after a long fight with leukemia or off the side of 8th Street stopped the presses. And while we already knew everything, true or not, by the time the paper came the next morning, it was still the only story at the breakfast table, on the bus, and in the teachers' lounge before school.

Well, if they got it right.

The newspaper usually did, a little slower and steadier as they set the type and waited for details to come rolling in. The radio, not so much. God bless our local radio station; they passed along info like a middle-aged book club, caring less about fact-checking than being first to break a story. A sudden all-points bulletin blasted over the shortwave, your (named) child killed in a gruesome rollover (of course on Black Diamond), ejected through the windshield and sliced to shreds. Meanwhile, said child is eating a second bowl of Lucky Charms, none the wiser. A little disconcerting for parents, a few questions while they second-guessed their religious ideologies and touched their kid's clothes and hair just to make sure. And somewhere across town the real parents hadn't got the news.

I didn't handle death well, myself. And I'd had a good long stretch between Grandma Olive and graduation that kept me satisfied on the mortality front. Still, I'd never quite shaken that last trip to the mortuary. Mom said it was important, "This is family. And you shouldn't be afraid of death anyway." I was six. Now, a normal funeral home might feel a little depressing, low lights and such, but even Chuck E. Cheese is depressing in Kennewick. So when Mom pulled into the parking lot I told her I wanted to stay in the car. "No, you don't. Let's just say hello to Grandma." Not "Grandma," but "Great-Grandma." The one I didn't know who sat in a kind of smelly yellow armchair, her walker doubling as a charcuterie board of pills and little candies; the one I'm not sure even knew my name. Yes, let's go say hello.

I've created a lot of the experience in my mind in the days since--an undertaker in Gomez-Addams getup, pale, unblinking, leading us down a long hallway that might otherwise look like a Holiday Inn except for the poor lighting and unfortunate motif.

"Here we are," he lilted, turning the key as if Grandma might escape. "Take your time. Enjoy yourself." Sure. Had he locked it behind us? The room smelled purposefully dusty, that kind of mustard-y smell that was a funeral package add-on. Grandma lay in the corner, not unlike I'd seen her in life, pursed lips and disapproving even in death. My mind floated back to Ray Bradbury's I Sing the Body Electric and the story of the Electric Grandmother, Grandma's black orthotics poking straight up out of the coffin as if recharging.

"You want to touch her?" Mom asked. It was a strange question, but I was six and of course I wanted to touch a dead person. "Look, she feels kind of funny. Her skin is hard like plastic. It's called 'rigor mortis.'" I looked up at my mother, waiting for permission, the mustard burning my nose. "Go on." I reached over the edge of the coffin and groped my grandmother's boob.

Until Matty died I didn't have to deal with death. I'd had a few bad dreams about Grandma's cold, freckled skin and the wrinkles that peaked but didn't move, but outside of the stop-off in Kennewick I'd dodged that bullet. The rest of my close friends and grandparents waited to die until after college, even my dog. And though I didn't know Matty and his brother well outside of staring at each other across the Thanksgiving spread or the occasional Easter pictures, I knew he was a good kid. He had some mysterious health problems that kept him small, but everything he lacked in size he made up for in a kind of after-school-special-happy-kid kind of way. Always a conversation and handshake with adults, a side-eye at kids he'd hope would include him in their games. But a good kid. We crossed paths back and forth until he graduated the year before me and either went to school or work, I didn't know.

That last summer before college I balanced love, and work, and life, and emotions, and all the delicious immaturity that is 18 years-old. And when I got a call from Matty out of the blue his voice sounded strange.

"Hey Ellie. Whatcha doing?"

"Nothing."

"Cool cool." The going-nowhere conversation from boys I'd learn to flag over the past four years.

"What do you want, Matty?"

"Nothing. Just seeing what you're up to." An uncomfortable feeling scratched at my senses; my parents were gone for the weekend.

"I've got to go." I didn't wait for him to answer before I hung up. But the phone rang again. "Hello?"

"Why'd you hang up on me? I just want to talk."

"What do you want to talk about, Matty?" my patience long gone.

"Want to go out with me?"

"No."

"Aw, come on."

"I've got a boyfriend."

"Pfffft I've got a boyfriend," he mimicked. I hung up the phone again, leaving it off the cradle to beep and die. At the far end of the kitchen counter my new Nokia cell phone buzzed, unknown caller.

"Hello?"

"Hey, quit hanging up on me."

"Matty? How'd you get this number?" His breath smiled on the other end.

"Your dad gave it to me." Dad, the teacher, always liked Matty more than any of the other boys I dated, and had a soft spot for kids with health problems. "Come on, Ellie. Come out with me. Just once, I swear."

"No."

"Can you see me? I'm waving." My neck prickled. I wondered if I locked the front door. Matty was a normal kid, but so was everybody until they weren't. I hung up again, turning off the phone. Maybe he could see me, but I didn't wait to find out, peeling out in my dad's truck.

And that was it, nothing more, nothing less. Another boy choosing creepy over sensible in the days before #MeToo. If he had any sense he'd stop calling or I'd have Dad change my number before I left for college. But I didn't have to wait to find out. The next day my parents came home early from wherever it was they'd gone, on the phone with Mom's friend Nancy, long calls at the back of the house. I sensed something was wrong when Dad pulled me aside in the kitchen.

"Matty died."

"What? Matty who?"

"You know, Matty." Oh, Matty.

"Died how? What do you mean he died?"

"I don't know. He took some girl on a 4-wheeler up to the Hills and they think one of those big logging trucks might've run them off the road. The girl's in critical condition, but Matty hit a tree. He's dead."

The brain is a funny thing. Twenty-four hours ago this kid had annoyed me, and I just wanted to go back to ignoring him like we'd done for all those years before that had worked so well. But now Matty was smashed up on the side of a wet logging road somewhere and suddenly I missed that stupid kid and wished he'd call me back. My phone hadn't even kept his number, just "unknown caller." I called a mutual friend. He'd asked her out too. I called another. Her, too. He'd called a long list of girls who said no, over and over again.

"What did he want to do? Where did he want to go?"

"I don't know," one of the girls sniffled, "something about riding bikes."

"Four-wheeling?"

"Yeah, I think so."

And there it was. In Matty's last day on Earth all he wanted was some girl to go riding with him. Not romantic, just companionship and to feel like someone would say yes for once. And the one girl who did was lying in intensive care, all plugged in to tubes and wires, a Jane Doe.

Death was always one of the options for kids growing up in my hometown. Not in a suicidal way, just a slice of the pie. We all had aspirations to do something bigger and better, or at least on our own. But small-town "bigger" isn't the same as city "bigger," and for a good chunk of the student population that meant babies that started cooking well before graduation, sometimes marriage, sometimes not, hard work that involved grease and sprays and skills you learned in your uncle's garage, struggle, addiction, and poverty.

But love was also a slice of the pie, and a pretty damn big slice. The kind of love that sets off a sexual revolution untouched by your religious upbringing or 7th grade chastity pact with your parents. The kind where you question your conservative politics for the sake of your friends, keeping those babies from cooking until after homecoming your senior year. Someone somewhere probably mentioned something about something, but in the back of a '94 Ford Escort you forget all that. Your only protection is that it's a coupe with a stick-shift and there's not enough room to get pregnant unless you really, really try. And who's trying?

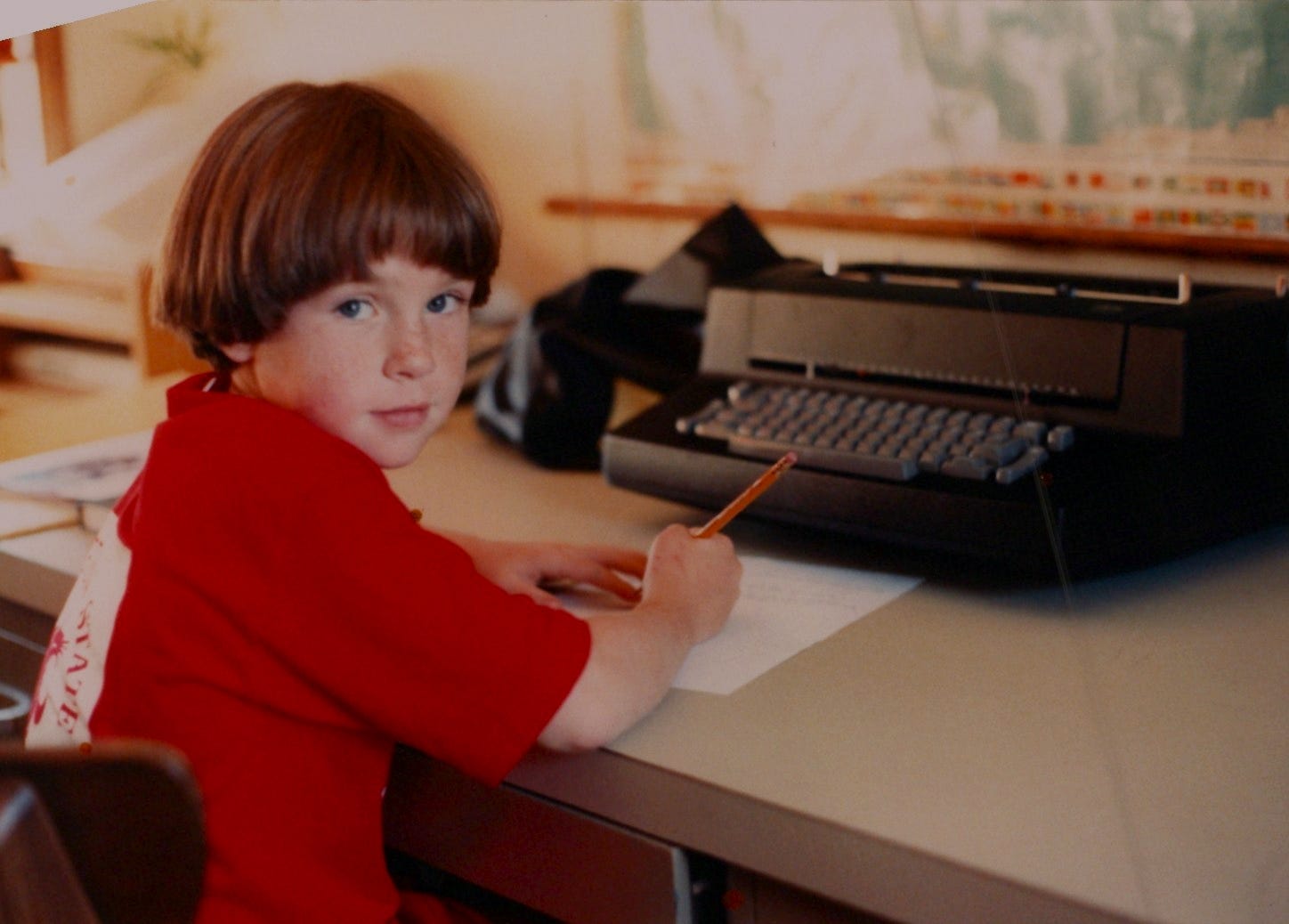

Now before you make assumptions about my love life and things I've seen, and done, and said, let's take a quick step back. Because I was a normal kid. I checked the boxes. I played the quintessential role of the "girl who liked boys." I never questioned my sexuality, the list of options unknown to me at the time, but I did try my best to fight off the feelings in an avid-tree-climbing-Ninja-Turtle-sketching-only-girl-in-school-with-a-bowl-cut kind of way. My time would come for all the "Dolly Parton crap," as I referred to it, but I'd hang onto the tomboy for as long as I could, again, never questioning the sexuality side of things. We'll come back to that.

Well written, and very relatable, Ellie. I’m in for the memoir!

Stories of PA I knew nothing about.