Though mostly true, I’ve changed this story and its characters just a bit for anonimity.

August first appeared in what felt like a dream, my 20s, clouded by bong hits and shady punk-rock bars, a time when we were all broke but had no qualms about conquering the world with our crummy community-college degrees and rebuilt Honda Civics. But August would lead that fight, some saying he won it in the end. I'd never seen him wear a shirt unless he borrowed it from someone else, and I wasn't sure if he had a house or really did live in a tent under the bridge in Ballard like people said. He had tremendous injuries that seemingly healed overnight, earning him the nickname "Wolverine," and everything about him was bigger, more interesting, and inevitably more shocking and illegal than anything I'd ever experienced, creating a sort of mythical beast out of the punk street kid that showed up unexpectedly then disappeared for months at a time.

Heroin is a helluva drug.

We shoved as many kids into one lease as possible back then, 12 to a 2-bedroom apartment, 18 to a house, stacked like sandwiches in the garage during the summertime. Landlords didn't care about the smell, the mess, the parking lot in the grass, as long as we paid the rent, preferably in cash. Half the guys lived in subsidized housing, turning their living rooms into recording studios and practice spaces for the revolving door of thrash metal bands. They all worked the same jobs at the same times, getting hired and fired in groups of 10 to 15, and everything paid under the table in cash, weed, hash, or bathtub whiskey. Between jobs they collected Unemployment, and anything after rent and ramen went to the hash business, which paid for guitars and better-than-bathtub whiskey. It felt like a good system as long as someone did the dishes (no one ever did) and no one died on the premises.

When August showed up he fit right in, a member of one of two groups: the Port Angeles kids and the Everett kids. PA kids, though we wouldn't realize it until later, had grown up with a silver spoon in our mouths compared to the Everett kids, who had something more like a spork. Our parents' blue-collar jobs were better than their parents no-collar jobs, living along an industrial speedway in the northern Seattle metro area. We had woods to hide in, campfires, lakes, all the romantic childhood storybook experiences that serve as a muse for a late-in-life writing career. They had 7-Eleven and shitty high schools, and shitty weed. We had beat-up Civics; they had bus passes. We had two parents; they were on their third step-dad. August fit the mold, at least on the outside, though there were rumors he came from money and stability. But we never asked.

August entered the room long before he entered the room. The kid didn't bathe. His body odor wafted, mixing nicely with their little hash business and weeks of dishes and warm, half-full cans of PBR stacked in towers underneath molding windows. There were sesh nights when August started out in apartment 73B (aka "band space 2"), and got so high on the landing outside the front door that he ended up on some foreign exchange student's couch. They poked him with a spatula, but no one called the police--we weren't a sanctuary state back then and there was no need to ruffle feathers. He eventually ended up back down the hallway, a wet cigarette in his mouth, and pissed on the coffee table before passing out again on the half-a-couch they found next to I-5 a couple winters before. They threw away the table, but one of the guys tattooed a stick figure on August's ribs to commemorate the moment. He also had a tiger skull that showed up every time he shaved his head. The rest were all scars.

It didn't surprise anyone that August was a cutter, though I don't think most of us noticed. He never had sleeves, if he wore a shirt at all, but we were too distracted by the bigger scars, the things he'd done while we were in the room. Like the time he baked a bike chain over a Bic lighter until it turned red, wrapping it around his arm and watching the oil sizzle into his flesh, adrenaline in his ice-blue eyes. He ripped it away, the skin coming with it, and didn't even wince. He relished the pain like drugs, pouring lemon juice on his wounds for an extra kick, and a day later had already begun to heal, just a scar and another pickup line when a girl in a bar asked, "what's that?"

I had a job at the Outback Steakhouse back then, and most of us worked in restaurants for the free food. August worked the fryer at Ezell's and the manager let him take home all the cold chicken at the end of the night. Word spread pretty quickly--most of the guys lived on ramen and SlimFast at that point--and there could be 25 people jamming, smoking weed, and eating fried chicken in the tiny 2-bedroom apartment by midnight. There wasn't a lot of room in the shared space, and August danced like nobody was watching. He sliced open a few kids one night without even knowing it, the raw chicken under his nails connecting straight with their bloodstream. Hours later ER docs drained lime-green pus from the red, crawling streaks that inched closer to their hearts. August handed them a half-drunk bottle of Ezra in a bag when they got home, and everything started again.

He was the first kid we ever knew who did heroin, though for a long time I didn't know if that was a rumor or how it all worked. He didn't shake or nod, and whatever conversation we had a month ago, or whenever it was we last spoke, he picked it up exactly where we left off. The only time anyone saw him out of control was booze, lots of it, booze and breakups. But booze was our thing, our heroin, the hardest drug we knew just a couple years out of high school. That would change a few months later, though I missed it myself, when the rest of the guys joined the oxy wave. But when August was high he was sober. He was "nice-guy August," calm and present. And more than one ex-girlfriend told me later that they preferred heroin-August because he could handle it so well. Anything but alcohol-August; alcohol-August was an asshole.

But August only ever had one girl who stuck around through his ups and downs, and she was loyal to a fault. Born on Cinco de Mayo, he'd found her in a trash can on the 4th of July, cowering and starving as the sky exploded with light. He named her "Django" after Django Reinhardt and "all the jazz," and she never left his side from that very first night, his child, his sister, his partner, his wife, his protector. On August's worst days she stood by, snarling at the EMTs who tried to Narcan him on the side of the road. If he was hurt or unconscious she'd find his friends at the bar, tugging at their jeans and pulling them down the block to find him passed out under a bush in the 7-Eleven parking lot. She knew what was normal and what wasn't, and never stood more than six inches from his side unless he told her to go.

Django loved music, and music loved her back. She slept on the edge of the stage every Friday night at Gallagher's, set after set, until August passed out somewhere on the floor or shooting up in the bathrooms. Then she picked him up and nudged him home to his little hovel one alley over. She wouldn’t eat unless he ate. She wouldn't drink unless he drank. But she never left his side. And if she was nowhere to be found, everyone knew he'd gotten home safe.

It's why we didn't worry about August when he disappeared for one, two, three, six months at a time. We knew it wasn't a bender or that he'd ended up in jail or dead, because Django would have found us and let us know. But she disappeared with him and we knew they wouldn't be back until it really started to get cold, long past Thanksgiving when he'd give his parents a call to let them know he was alive and okay somewhere in Canada or on the East Coast, Arizona, California, wherever he'd ended up. Because August, like most transient kids from Seattle, and anywhere I suppose, hopped trains and traveled all over North America. We later learned that it was some of his soberest adventures, times when he kept a journal and met people from all over the world who'd escaped life in the burbs for the great journey.

Maybe they were all addicts like him, and sometimes you could get a fix here or there in this underground community of homeless kids in every state and at every stop. But inconsistent drugs are worse than no drugs at all, and no one wants to go through withdrawals in a dark tunnel somewhere without food or water.

They all brought their dogs, because as August had told all of us at one time or another, "You never travel without a dog." Maybe it was for his protection or to keep wandering hands out of the only things he had. But I'd heard dogs kept the kids alive, warm, and awake if they needed to be. There were long stretches of tunnels without air, and if the trains slowed down you could easily pass out from the exhaust and never wake up. The dogs were better at staying awake, keeping their owners alive and holding their breath. And if the weather turned cold too early a kid could freeze in an empty train car, especially if the brakes seized up going over a mountain pass, which they often did. The dogs kept their owners just warm enough to survive, splaying themselves across the sleeping kids on the hard car floor.

This wasn't Amtrak, and never meant for humans on a sanitary or safety level, but the operators rarely kicked them out unless they caused problems, pretending not to notice. Still, they worried about those long, long tunnels, wondering how much air the kids had left 100 cars behind.

Django learned to fly, a nose-diving into an open stacker before August ran to catch up. As a result, she developed arthritis in her joints, but never complained of the pain, always ready for one more trip. One time he'd picked a bad car, one with a "suicide bucket" on the end that had no floor, and watched in horror as she slid beneath the train. He caught her back leg just in time, pulling her back onto the platform. He should have known better--those cars were only for experienced jumpers. Had he not been sober...

They said August fell in love with a woman in Montreal and she became his reason for disappearing from the Northwest every spring. She spoke Polish and wrote him letters, and he came back to Seattle fatter and happier, Django too, before reverting back to a life of heroin and punk rock. No one knew her name, and no one could imagine August settling down with a "square chick," taking showers and listening to Panic at the Disco and acid jazz. Rumors are rumors, but I wondered if he didn't belong in that life more than this one. American August was hurt and addicted; Canadian August was not. Every so often the Canadian border patrol tried to send him back, but he didn't own an ID and America didn't want him either. A "metaphor for [his] life," he used to say, lighting a cigarette.

But he came back just in time for the holidays, a hug and kiss and some cheap stolen shit wrapped in a plastic grocery bag that he handed out to his family in front of a brightly-lit tree. He met their low expectations, and he met ours, high and drunk and flying into traffic, punching out rearview mirrors of nice cars, and threatening to fight asshole frat boys who wouldn't kiss their girlfriends on New Year's Eve. Of all August's personalities I liked that one the best. He never stood by and watched a woman be mistreated or ignored, fighting anyone who crossed a line and calling cabs, walking girls home, or skimming a little off the top for himself. He called it a "perfect week:" 7 girls in 7 days.

"I'm tired," I remembered a girl saying to him once, reaching for him down the bar.

"Okay, that's fine, I can molest you later."

I found myself sitting back and watching August live, or the part of it I saw, observing how he interacted with friends, the way his body entered the bar, picking up on little mannerisms that I don't think anyone else noticed. He wasn't a big guy, maybe 5'6 or so, but stood a little shorter until he saw someone he knew. And even then his guard was up until a couple of well drinks in and a trip to the bathroom. He did better in a crowd where he didn't have to be connected to any one person, and it dawned on me that I never saw him one-on-one or even knew who his close friends were. I certainly wasn't one, just an acquaintance, though his adrenaline and hyper-focused conversation made me feel valid and heard. But maybe that was the drugs. I was just a kid back then and comparatively sober, so I just saw it as his personality and intent. I think I still see it as his intent.

But the more I watched him the more I saw a kid who didn't trust himself, or maybe didn't trust anyone else, though he pretended to. Heroin kept him separate, and the only people he allowed in were other addicts. And outside their small circles in back bedrooms or disabled bathroom stalls, he didn't trust them either. And though he seemed to have a sort of "chosen family," he wandered alone a lot, except for Django, and no one spent a lot of time looking for him. Once in a while I'd remember not seeing his face, wondering if he'd hopped on a train a week ago or a couple of months, but then I'd go back to practicing being a grownup and forgetting all about the smelly punk-rock kid who made me feel whole.

There was one old guy though that I know August trusted, a sort of older version of himself and the least-judgmental man I'd ever met. He went by "Schwinn" and I think lived in the same apartment with August and maybe a partner or wife, though I'd never been there. August saw him as a mentor, and though he was never sober for more than a few weeks, Schwinn either, the two of them maintained one of the more stable relationships in August's life. His time living in Schwinn's downstairs apartment are the days I've wondered the most about since, something he kept from all of us while living addicted in the spotlight, addicted to the spotlight, and relishing the image of a street kid asleep on a bench somewhere. But inside that little apartment was his real life, and none of us were welcome there.

Eventually we all grew up, finished school, and got "real" jobs, though at the height of the Recession we still couldn't make any money. But adult poor felt better than trashy kid poor, and now we washed the dishes and learned how to pay our bills without calling home. I married a punk drummer and moved into a sweet, crummy little apartment where we had our first baby, and life started to become what I'd planned over tea parties and Cabbage Patch dolls. And maybe I didn't think about August, or maybe subconsciously I knew I wouldn't see him anymore, but I washed my hands of the band practices and breathless bars, and turned all my focus to raising my daughter the best way I knew how. A mention on Facebook or in passing would remind me that August even existed, but remembering that he lived below a bridge now was something of another lifetime. He'd somehow made it onto an episode of MSNBC's "Runaways," and looked just how I remembered him, and I felt smart, even better-than, from the comfort of my clean two halves of a couch, in my clean house, dinner on the stove.

Just before Christmas that year the rumblings about August got a little louder across social media and in the smaller circles that still met at Gallagher's on Friday nights. He hadn't called home on Thanksgiving, and now his mother was calling around to hospitals and police stations trying to find him. But where do you look for someone who could be anywhere, who's not interested in being found? Maybe he'd really done it this time, taken a little too much and overdosed in the back of a frozen stacker. Maybe that wouldn't have mattered if he'd brought Django, but he hadn't this time. And you "never travel without your dog."

Django had grown old and fat, and as much as she loved August even she didn't want to go anymore. He left her with friends, hugging and kissing the old mutt and promising to see her soon. But in hindsight everyone who witnessed their good-bye said something felt off, that this wasn't a "see you later." His closest friends told him not to go, that maybe the last time was really the last time and now he needed to stay home, get his life in order, grow up a little. She needed him here. But he promised, kissed her again, and left to find his adventure. Maybe a woman. Maybe just peace. Maybe nothing.

By the time we all figured out that August had gone missing his mother had been searching for him for weeks, the panic beginning to build on days two, three, and four after the missed call on Thanksgiving Day. We were all so disconnected from her and his other life—the Mormons, the money, and the place where he kept a closet full of clothes. I'm sure she wanted nothing to do with an endless lineup of punk kids who enabled her son, but at some point she picked up the phone and called one, then another, then another, searching for her little boy. Then it was social media. Then benefit concerts. I didn't know how money would find August, but someone passed around a hat and everyone picked up a flyer with his face on it. Like we'd find him here, missing in his own back yard.

We didn't find August, but someone else did, his body ending up in a morgue in rural Wyoming as a John Doe, toe-tagged and shoved in a drawer, waiting for a phone call.

Much of August's story from before, during, and after the day they found him next to the tracks is a mystery, even to his closest friends. Some say a fight broke out and one of the kids pushed him from the train, though I'm not sure how anyone would know. Others said he overdosed, the likeliest scenario, and a track laborer found his body, but only his torso. They said he'd been eaten by animals or dismembered by the elements. By the time law enforcement connected his mother with the John Doe in Wyoming the only thing they had to identify him was a small tattoo on his ribcage, a stick figure pissing on a table. She'd never seen it before, and it passed around private chats and texts until someone got the courage to tell her it was August, the night at 73B forever memorialized on his mottled, gray skin.

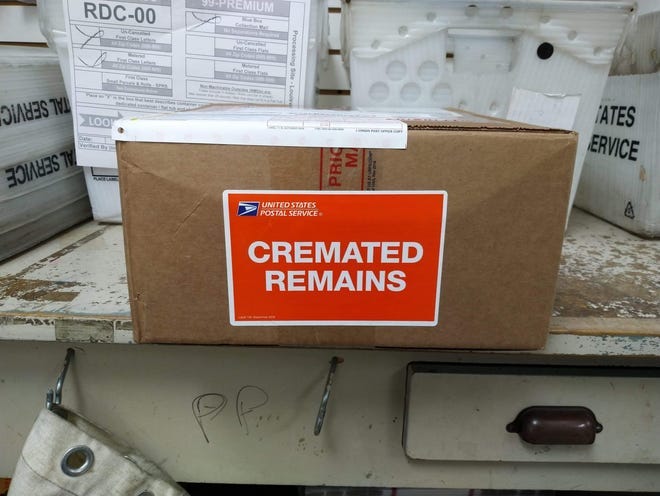

The Albany County Police Department sent him home in a Tupperware, labeled "cremated Remains Reg. No. 0423." A week later Django stood on the beach watching her master float out to sea on a small wooden Viking ship, set fire at sunset as every friend August ever had (including his mother) took a shot of Ezra and said good-bye. I learned later that not all of his ashes sank to the bottom of Puget Sound--a good handful was melted down into glass pipes and random pieces of jewelry and memorabilia.

And then we all just walked away.

Over the next decade our little group transformed the leather and hair dye into going back to school and raising families, working for real jobs with a pension and insurance, finally giving our parents a full night's sleep. Some didn't. Some continued to ride the wave of the ever-changing drug scene in a port city, replacing one addiction with another--China white, to oxy, to fetty--keeping "straight" their only high bar; denial their warm blanket. A few died, but never with the impact August had. Just a quiet post on Facebook and that sort of sunken feeling that heals in a few days.

But I never forgot him, even when I was sure everyone else had. I wanted to know who he was, like really who he was, and why he'd spent so much time on freight trains going back and forth across the country. I wanted to know what happened, if the Albany County Sheriff's Department had any information on how he died, or if he was just a number, another dead homeless kid frozen in the snow. I called friends, sent emails, did my best to track down names, dates, and locations, but everything I found was a dead end, and every story contradicted the last. For a kid who'd spent much of his adult life running from the cops, he didn't seem to have a record, or even a birth certificate. A ghost. I'd need to do this differently.

And so we sat down, one person at a time, and I listened to August's life story in fits and starts, in bits and pieces that didn't fit together like a puzzle, more like broken glass. Some missing. Some so vague and fragile it had all but become forgotten. Truly the mythical unicorn we all knew him to be.

Gideon August Delgado was a military kid born at the end of his father's career and his parents' marriage, in late summer 1980. He'd picked up his step-dad's name around us, Jones, because the guy didn't hit like his real dad did, and the police had too many Joneses in the system to care about his stupid crimes. No wonder I couldn't find a record; I'd never known his real name. After his parents split his mom joined the Mormon church looking for stability for her kids (August had an older sister), and did her best to work a couple jobs and raise them in a good school district in Snohomish County. When the step-dad came along, probably a guy from church, his mom quit one of her jobs and signed August up for piano lessons and art classes, hoping it might work better than the therapy he never went to.

August was a smart kid. He did well in school and played a lot of sports. And if you know where to look you might find a football trading card with his face on it floating around, the ice-blue eyes in focus and arms without scars. Just a regular kid, in a regular town, with a regular family. No one really knows when things changed or if something happened. Or if they do they're not saying it. And if I do, I'm not saying it either. But whatever it was, he walked away from all of it, preferring psychedelics and hazy basements. Heavy teenage relationships and found family felt better than a future in accounting, or whatever the hell Mormons end up doing for a living.

And when he got hooked on heroin, we didn't know. When he got Hep C ("just a little bit") we didn't know. When the local PD fitted him with a pair of "police teeth," we didn't know. But by the time we all showed up he was just the stinky, funny, and very clearly emotionally-scarred kid that we didn't question. And by the time he was gone, we wished we had.

When August's landlord didn't hear from him in three months he opened up his apartment, a little worried he may never have left. But no one expected to find the world August left behind. In his closet-sized flat, one of just two he'd had as an adult, and without a bathroom, August's small bed lay pushed up against one wall, clean and made. Over it he'd nailed milk crates side by side, and one over the other, in a grid that encompassed two full walls of the tiny room. One wall held every classic novel you can imagine, packed snugly together like Jenga. The Scarlet Letter. To Kill a Mockingbird. The Count of Monte Cristo. In Cold Blood. Hundreds and hundreds of books, each weathered and flimsy from reading over and over again, no doubt with the flashlight he'd left by the bed. Next to his pillow was a beat-up copy of Maniac McGee.

On the opposite wall was all spiral notebooks, again, packed so tightly you could hardly pull one out. Half he'd filled with comics, and drawings, musings, and a sort of artistic documentation of his highs and lows. The other half was writing, though very little of it was any kind of journaling or "dear diary." These were stories, long stories, with chapters and conclusions. Underdog characters who achieve wild success, if only in their own right. Or at least that's what I imagined them to be. Another rumor I would never track down--all the journals somehow destroyed after his death.

He'd left a box of letters under the bed from a woman named "Elzbieta," the envelopes postmarked from Montreal. These someone did save, though I haven't read them and can only summarize her correspondence. Her father owned some kind of local eatery, Polish food from the sound of it, and Elzbieta spent a lot of time trying to convince August that he was welcome there, despite what "Ojciec says." The letters were from long before August's death, maybe even before he'd become who we had all known him to be. But whoever found them said that they were written in Polish, and that August had made little drawings in the margins, happy faces and excited bouncing stick figures, and that he'd kept a pocket Polish-English dictionary on a small school desk. The letters stopped a couple years later, and after that there were only two from August himself that had been returned to sender, unopened. I wondered what they said, if this was the break when he'd sliced open his arms with a straight razor and poured the lemon juice down them for the first time.

The only other thing in the box was a polaroid of a scruffy looking puppy with a patch of hair missing up the side of one of her legs. August, younger then, lay next to her on a pillow in a Miller Lite shirt, side-eyeing the sleepy pup. On the back, the date in Sharpie, only six or so months after August's last returned letter. Just enough time to learn to be a junkie, and not enough time to heal.

He had no food in his fridge. He had no drugs anywhere. And his high school letterman jacket hung in a garment bag on the back of a chair. He had two balled up pair of clean socks, and above his bed he'd lined the ceiling with CD cases. Toots and the Maytals. Grandmaster Flash. Tom Waits. Panic at the Disco. Wu-Tang Clan. Any other space he'd filled with punk show flyers, all of his best friends' shows, and not a single one that he'd ever missed. The greatest fan.

When August's body was found his landlord stopped tallying the missed rent and packed up what he could, though August had never mentioned family, and with the heroin he'd never brought friends or women home. Maybe that's how everything ended up being destroyed, though then how would I know what I know? Or maybe I don't; maybe it's just what I've imagined.

August's friends told me stories, sent me pictures and documents, and slowly I began to piece things together. With the information about Albany County I reached out to the Sheriff's Department to see if I could track down more information. As it turns out, no one knew what happened to August, not even his closest friends. His death was still a mystery ten years later. It would be another eight months before I heard anything back, and then a quiet game of tug-of-war trying to access public records. Meanwhile we waited, assuming the most dramatic, and exciting, and August-like ending.

It was none of these.

Albany County Sheriff's Office

Deputy Report for Incident 15-064465

November 2, 2012 07:02 Hours:

Sgt. Muse notified of male subject on the railroad tracks 16 miles southeast of Bosler. Appeared to be asleep, possibly intoxicated.

07:27 Hours:

Ambulance dispatched though subject is deceased. Coroner dispatched and pictures taken of male who is lying face-down between the tracks. No identification.

After speaking with the railroad manager, it was determined the train would have been traveling 50-70mph. Blood around the scene shows the decedent's body moved before coming to its final resting spot, likely landing first in a rocky patch next to the tracks. More blood found at a distance of 2.63 miles from the scene, leading up to the scene.

Subject has many cuts and abrasions, and a dislocated right shoulder, but is absent of stab wounds or bullet holes. A toxicology test came up negative, and there was no evidence of alcohol at the scene.

After several return visits to the scene by local PD and railroad personnel a large amount of cotton stuffing and pieces of dark blue ripstop nylon were observed and collected, suspected to be from a sleeping bag. Several pages from a book were also discovered near the same area, though it is not clear if they are connected to the decedent.

There were more details, codes and transcripts, information about the railroad guy who found him, and requests from Snohomish County PD for the full report. But I had everything I needed to go back and tell our friends what really happened to August, hoping that they still wanted to know.

They did.

August hadn't died from being pushed out of a speeding train car. No one had beat him up or killed him before throwing his body onto the tracks. He hadn't been high. He hadn't been drunk. And the book was his, 16 pages from a copy of Into the Wild. Most were wet and illegible, but near the top of one he'd circled "I am reborn. This is my dawn. Real life has just begun."

I hope that's the last thought he had before he fell asleep somewhere crossing southern Wyoming, no dog to keep him warm on the frigid November night, just a dark blue sleeping bag wrapped tightly around him as he edged closer to the open door. When he fell, he awoke, reaching frantically for anything to hold onto, ripping the flesh in his shoulder until he had to let go. And somewhere between Earth and heaven the sleeping bag caught on a corner, a wheel, the bucket, and dragged August nearly three miles down the tracks, going 50 to 70 miles an hour. They said he probably hit his head on the way down, that it was quick, and I've only ever let myself believe that they were right.

But he came to a stop, the bits and pieces finally giving way, and laying him gently between the tracks, asleep. Not a dismembered torso. Not an unidentifiable shred of meat. Not eaten by animals or frozen under the snow until the spring thaw. Just a kid who ended life on his own terms, in a way, and dispelled the myths of who we'd written him to be. The heroin addict. The junkie. "Wolverine." The unpredictably, slightly extraordinary, smelly kid. The unicorn.

To my friends, I hope this closes a chapter of our lives that we lived with zeal, and fury, and never-say-die. A time of immortality and immateriality, life of so little that felt like so much. A world of found family and fame in a community so tight that it's hard to believe we've all blown away on the wind. I sometimes wonder if August would have blown away, too. Or maybe that's just what he did.

Ellie is an author, editor, and owner of Red Pencil Transcripts, and works with filmmakers, podcasts, and journalists all over the world. She lives with her family just outside of New York City, and is represented by Vicki Marsdon at High Spot Literary.

What a beautifully written story. Thank you for sharing that. One of my favorite shows on NPR was Selected Shorts, a long time ago. My son would hear this before he even arrived as he was safely snugged in my womb. And for years we would listen at noon on Fridays. This coupled with me reading Harry Potter out loud , I believe, gave him his love of reading and story telling.

It’s been 5 long years since I’ve held him, heard his melodic voice sing or laughed uncontrollably at an inside joke between us. Heroin isn’t what killed him but he had his moment dancing with the devil. So much of your story resonated with me and the struggles of addiction. To pay homage to your friend in such an open wound kind of way is healing. His last words of being reborn is maybe most telling of his ending. Maybe he learned what he came here to learn and it was simply time to start again… another life, another lesson. Finally, You have no reason to suffer from imposter syndrome, you are truly talented.

This is such a fine piece.

What fascinates me is (in a way) it shouldn't work. It's all back story of a sort, though as a non-fiction essay, or memoir, that what those are. Yet, this works as a story because of a clever structure that has its own form of escalation.

It's set-up almost like a mystery, as the narrator goes deeper into the truth of who August was. It's like a Citizen Kane rosebud thing, where we are propulsed through the story by this larger (and at the same time) smaller than life character. Who really was August? It's a question that we could pose about each other. How are we really known?

When the apt. full of classic books is found it makes sense, the storytelling has led us to a revelation that makes us consider what we thought before, and rather than a jarring surprise, we go... of course. The same when we read of the letters and love he had for Elzibeta (sp?) - and another revelation of where August's pain and scars came from - both the physical ones and the mental ones.

This is a story that will stick with me. It's a gift that you've put it on this platform. It deserves to be read by many people.